|

Ice Caves of Montana

Above: This ice cave is located near Crystal Lake in the Big Snowy Mountains of central Montana, about 25 miles south of Lewistown. The photo was taken in August of 2009. The columns behind me are solid ice and I am standing on ice. CLICK HERE to watch a 5-minute YouTube video of my trip to this cave.

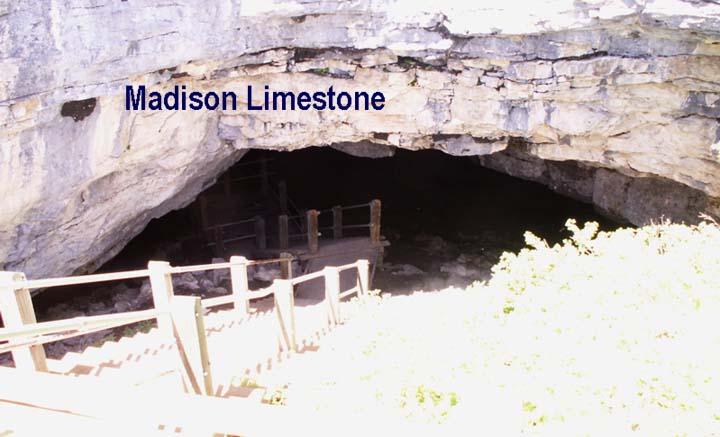

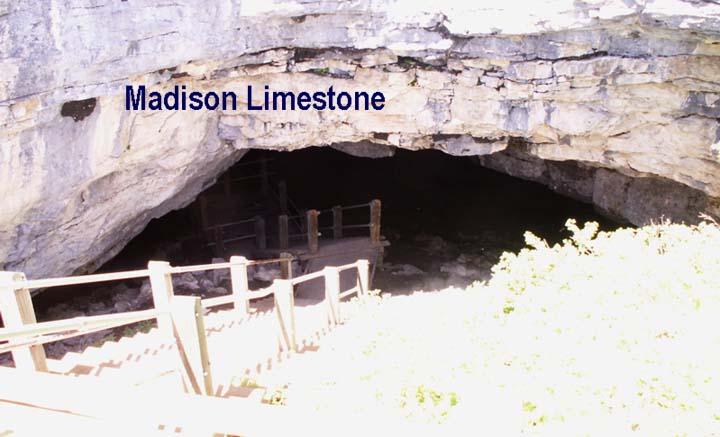

Below: This photo shows the entrance to an ice cave located in the Pryor Mountains, south of Billings. This one is simply called "Big Ice Cave."

CLICK HERE to watch a 2.5-minute video of my June 2009 trip to Big Ice Cave.

Although there are others scattered in the mountains of central and eastern Montana, the ice cave near Crystal Lake (top photo) and Big Ice Cave in the Pryors are two of Montana's most popular ice caves. Most (perhaps all) ice caves in the state are found in a rock formation called the Madison Limestone, which has been described as a

'geologic Swiss cheese" due to it's many caves and sinkholes. In fact, Montana's most famous cave, the Lewis and Clark Caverns, was formed in the same Madison Limestone as the two pictured above even though vast distances separate the three.

So what's an ice cave?. . .

Contrary to what you might think, the kind of ice cave featured here is not a cave formed in ice, but rather a cave that remains cold enough to contain ice all year long. As you saw in the video, smooth ice at least several inches thick covers the floor of Big Ice Cave. The air in caves is almost always cooler than air outside during summer, and warmer than outside air during winter because caves are well-insulated by the thickness of rock around them, however very few stay cold enough for ice to persist through the hot months of summer. So, what makes some caves so cold? . . . There are two factors involved.

1. It's a density thing . . .

Whether you are studying geology, meteorology, oceanography, or astronomy, one of the most important underlying principles is "density". Density also plays a crucial role in the persistence of of ice in some of Montana's caves. Since molecules of cold air move slower than those of warmer air, colder air molecules tend to be closer together. This makes cold air denser (heavier for its volume) than warmer air. As a result, cold air tends to sink to the lowest location . . . In this case, the bottom of the cave.

2. Where do you keep your ice cream? . . .

When it comes to storing frozen foods, there are two basic types of freezer compartments. There is the kind located along the bottom, top, or next to the refrigerator compartment. To get frozen foods from these, you simply open a door. But as you do, the cold air inside flows out onto the floor and is replaced with warmer air from the room. After you shut the door, electricity is used to re-cool the air so your ice cream doesn't melt. These freezer compartments are like normal caves.

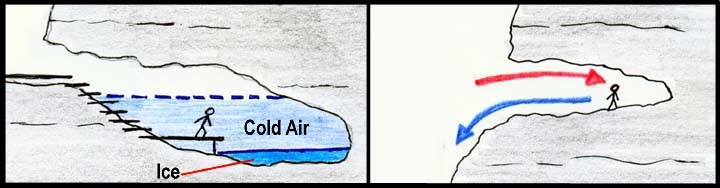

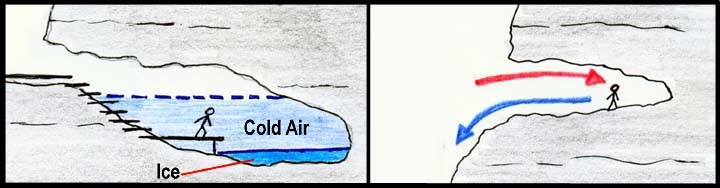

The second type of freezer compartment, which opens from the top, is much more efficient because when you open it the cold air does not easily escape. Sometimes called "chest freezers", "freezer chests", or "deep freezes", these are similar to ice caves. Ice caves are laid out in such a way that the entrance to the cave is located above the cave, so cold air doesn't flow out. Like the chest type of freezer, the opening to an ice cave is above the place where cold, dense air sits undisturbed.

Below: In the ice cave (left) there is no outlet for the cold, dense air from the previous winter. In the normal cave (right) cold air spills out and is replaced by warmer air throughout the spring and summer.

Good news, bad news . . .

Although the Big Ice Cave is only about 40 miles south of Billings, the driving distance is closer to 80 miles, and the road is very bad in places. . . . The seven-mile stretch that crosses the southwest corner of the Crow Reservation took over 30 minutes in my Toyota Corolla, and the last few miles before reaching the cave were extremely rocky*. In all, the trip from Billings to the cave took over 2 hours. The "silver lining" here is that the long distance and adverse road conditions discourage people from visiting the cave. If the cave were visited by massive amounts of people, (I think) this might cause the cave to get warmer because every time someone goes down to the viewing platform, they cause a little warm air from outside to mix slightly with the cold air that sits in the cave. On the day we visited Big Ice Cave, the temperature outside was 80 F. As we walked down into the cave the boundary between the warm air above and much colder air below was very distinct.

*If you go to the cave, drive a high clearance vehicle (not a Toyota Corolla) and do not go if the road is wet!

Terms: limestone, convection

|