|

Helena has its

faults.

Photo courtesy of Mike

Stickney

Montana Bureau of Mines and

Geology

A torn surface . . .

This aerial photo shows the western edge of

the Helena Valley just a few miles north of

Helena. If you look closely you can see an

elevation change in the surface along a line

between (and parallel to) the railroad tracks

and Green

Meadow Drive. If you can’t tell where it is,

scroll down to see the labeled photo near the

bottom of this page. The linear feature, called

the Iron Gulch fault scarp, is where the ground

surface has dropped three to four meters

above a “normal fault” as a result of

earthquakes over the last 130,000 years. It is

not known how many quakes it took to form

the Iron Gulch scarp, but it could probably be

determined by careful study if a trench were

dug across the scarp.

One quake at a time . . .

One quake at a time . . .

Earthquakes happen when there is movement

along a fault, however, not all movements

cause scarps to form. For example, during

the historic quakes that rocked Helena in

1935-1936 there were no surface ruptures. In

contrast, a big earthquake near West

Yellowstone in 1959 caused several new

scarps, including one that was 14 miles long

and as high as 21 feet (see Hot Link below).

Like most fault scarps, the Iron Gulch scarp is

not in solid rock, but rather in gravels and soil

above the bedrock. The actual fault is located

within bedrock, buried beneath soil and

hundreds of feet of gravel.

Map courtesy of Montana Bureau of Mines

and Geology . . .

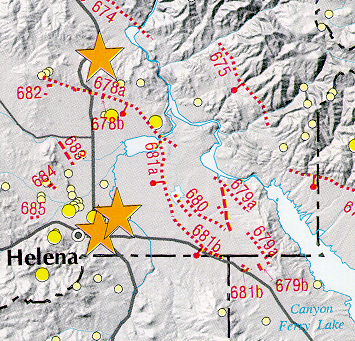

The map at the right

shows faults (dashed lines) that have been

identified in the Helena area as well as

post-1982 epicenters (yellow circles). The

stars mark epicenters of post-1900

earthquakes with magnitudes of 5.5 or

greater. Some geologists believe that the Iron

Gulch fault (#683) extends to the southeast in

the subsurface, all the way to East Helena. All

of the faults shown on the map played a role

in the formation of the valley. Like many

basins in the northern Rockies, over millions

of years, the block(s) of bedrock that the

Helena Valley sits on has dropped down one

earthquake at a time along these faults to

form a basin surrounded by mountains (called

a graben). Since its formation the Helena

Valley has filled with gravels, sands, and silts

washed down from the surrounding

mountains. As Helenans learned during the

1935 quakes, structures built on these deep,

loose sediments shake much more violently

than structures built where bedrock is not far

below the surface.

.

Supported by Internet

Montana

Supported by Internet

Montana

Terms: graben, normal fault

|